©Alexandra Chambers | Neurotopia CIC | October 2025

All research is available for PDF digital download on: https://studio.buymeacoffee.com/extras and all money goes directly to Neurotopia CIC to fund further research, thank you.

Abstract

Autism is widely classified as a neurodevelopmental disorder, yet accumulating evidence suggests it represents a modern diagnostic label applied to evolutionarily conserved, genomically divergent traits. This paper presents a cross-disciplinary research synthesis examining the biological foundations of autism through molecular genetics, neuroimmunology, mitochondrial medicine, pharmacogenomics, and systems biology. Studies were selected for relevance to structural and regulatory variation – including redox pathways, immune signalling, ion channels, fatty acid oxidation, and environmentally sensitive epigenetic mechanisms. The synthesis supports a two-stage model of divergence: Stage one reflects ancestrally inherited variation across redox, immune, metabolic, and neurophysiological domains, conferring differential responsivity to environmental input. Stage two involves cumulative toxic or inflammatory stress during sensitive developmental windows, resulting in epigenetic disruption, mitochondrial collapse, and phenotypic regression in susceptible individuals. This model distinguishes stable genomic traits from acquired harm and highlights the risk of conflating systemically induced preventable injury with intrinsic identity. Findings demonstrate that what is currently pathologised as autism may often reflect adaptive human variation rendered incompatible by industrial exposures and systemic neglect. In this context, autism emerges not as disorder, but as the disrupted expression of distinct biological architectures shaped by ancestral environments. A revised framework is proposed in which phenotype is recognised as the emergent interface between inherited genomic configuration and environmental compatibility, requiring system-level accountability in both classification and intervention.

1.Introduction: Rethinking Phenotypes

The term autism has long been a contested clinical descriptor for a constellation of behavioural traits, stratified through psychiatric diagnostic systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)1. However, there is mounting evidence that the label itself obscures rather than elucidates the biological diversity that it attempts to categorise behaviourally.2-4

Several authors have challenged the explanatory power of categorical autism diagnoses due to their failure to account for within-group heterogeneity.5-8 Waterhouse, in particular, has proposed transdiagnostic endophenotypes as a path toward more mechanistic clarity.5 While this paper shares the call for a reframed model, it departs from behavioural frameworks altogether and instead urges for systemic accountability and foundational reformation.

Existing psychiatric frameworks identify autism as a discrete neurodevelopmental disorder, yet this framing fails to account for the complex, multi-systemic differences present in the individuals who receive the diagnosis.9-10 This research proposes a reframing of autism as divergence – a biologically grounded, environmentally modulated profile underpinned by distinct genomic, physiological, and metabolic architecture.

This reformation proposes a two-stage – and often middle grounded – nuanced presentation of understanding divergence; Stage one is characterised by ancestral retained evolutionary genomics and divergent architecture that confers altered responsivity to environmental inputs. Stage two involves additional and cumulative harm to those divergent genomics – acquired through environmental mismatch and/or systemic neglect. Thereby resulting in the manifestation of traits diagnostically associated with increased risk of disability, often termed as level 3 or ‘profound autism’. This distinction between these stages can be substantial – astronomically wide, and also dependent on environment factors – hence, ‘autism spectrum’. This integrated model is positioned as a necessary counterpoint to emerging phenotype-stratification efforts, which risk dangerously misclassifying stress-induced traits as fixed and innate, while failing to account for the systemic, epigenetic and environmental modifiability of expression.

This synthesis addresses the broader question of scientific accountability beyond the scope of revised analysis. Diagnostic constructs do not exist in a vacuum; they inform clinical practice, educational policy, public health guidelines, and social perception. When classification systems are built upon incomplete or exclusionary models – particularly those that omit genomic-environmental interaction – they risk causing real-world harm through misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and systemic neglect. This work therefore aims to advance not only a more biologically coherent understanding of divergence, but also a more ethically and scientifically responsible approach to classification, intervention, and research design.

1.1 Background: Autism and Terminological Clarification

The diagnostic term autism is not a fixed biological entity but a historically and institutionally constructed diagnostic category. First coined by Eugen Bleuler in 1911 to describe withdrawal in schizophrenia,11 the label was later appropriated by Kanner in 194312 and Asperger in 194413 to classify atypical patterns of social and communicative development in children. However, these early definitions were both narrow and shaped by cultural and ideological biases.14 The formal recognition of autism in the DSM-III in 1980 marked the beginning of its modern diagnostic life,15 yet the criteria have undergone repeated revisions – demonstrating the inherent instability and social contingency of the diagnostic label.16

Despite the categorical framing, converging genetic studies confirm that ‘autism’ reflects a highly heritable, polygenic architecture and is characterized by complex neurobiological variation.17-19 This paper challenges any inherent or behavioural ‘disorder’, and explores the genomic architecture that forms a valid individual profile of cognitive and sensory uniqueness. This divergent architecture spans six interrelated domains: genomic,20 metabolic,21 neurological,22 immunological,23-25

physiological21,26 and epigenetic.27-28 For these reasons, and in recognition of the limitations of the autism diagnostic construct, this paper will refer to the specified demographic as divergent, where possible. This terminological shift is epistemological – grounded in an ethical commitment to scientific accuracy, biological nuance, and liberation from deficit-based psychiatric narratives. This is also to maintain internal coherence with the multidimensional biological model proposed herein.

2.Heritability and Environmental Modifiers

Autism is one of the most heritable of neurodevelopmental profiles, with twin studies estimating genetic contributions upwards of 80%.29 Autism is polygenic, there is no single autism gene. Large-scale whole-genome and exome sequencing studies have identified hundreds of rare and common variants associated with autistic traits.19,30 These genes cluster into functional categories involving synaptic development,20 neuronal migration,22 mitochondrial metabolism,23 and immune regulation.24-25 The high heritability of these traits29 challenges their continued pathologisation, as evolution does not consistently preserve neurological genomic architecture without functional or adaptive significance.31-32 Despite this expanding genetic landscape, the mechanisms through which these genes interact with environmental signals remain significantly underexplored – particularly in real-world contexts where epigenetic and metabolic stressors are ubiquitous.33-34

Although often termed ‘de novo,’ many of these variants may emerge from environmentally induced genomic instability, particularly in individuals with compromised methylation, redox, or DNA repair capacity.35 In addition, the framing of autism as genomic autosomal recessive inheritance also reduces genomic variation to pathology, omitting its foundational role in evolution. Evolution itself depends on variation to advance; without it, there can be no adaptation, no emergence of new adaptation or improvement, and no human evolutionary progress.32 To pathologise inherited variation not only misrepresents genomic diversity, but reinforces deterministic narratives that undermine the logic of evolutionary biology.

An important distinction must be made between evolutionarily conserved genomic variants – representing stable, inherited architecture – and the often-co-existing modifiable variants that may be disrupted through environmental exposures. Evolution depends on variation to move forward; it is the substrate of adaptation, maintained by selection pressures and functional constraint36-37 However, environmental insults such as oxidative stress, toxins, and systemic dysregulation can induce mutational or epigenetic changes.38-39 These can lead to functional impairments that may be mistakenly interpreted as resulting from purely genetic traits.40 Without the ability to differentiate adaptive divergence from environmentally induced dysfunction, science risks continuing to pathologise evolutionary diversity itself – undermining both biological resilience and the very mechanisms by which adaptation occurs.41-42

It is well-established that epigenetic regulation – including DNA methylation, histone modification, and microRNA expression – play a pivotal role in neurodevelopment.43 These mechanisms are particularly sensitive during critical periods of brain development, such as the first three years of life.44 Exposure to environmental toxins, infections, or immune-modulating pharmaceuticals during this window can permanently alter neuronal function, especially in individuals with underlying metabolic differences.21, 45-47

The 2004 landmark study by James et al. demonstrated that autistic children had significantly lower levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) and elevated markers of lipid peroxidation, indicating a systemic redox imbalance.48 These findings align with subsequent work highlighting the convergence of elevated oxidative stress, immune activation, and mitochondrial variations.21,48-51

3.The Oxidative Stress Cascade and Mitochondrial Vulnerability

A growing body of literature confirms that affected divergent individuals exhibit biological signatures of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and metabolic irregularity.21,52 These are not isolated abnormalities but part of a systems-level crises that can become especially pronounced during early development, when energy demands and synaptic pruning processes are at their peak.

Oxidative stress arises when the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) exceeds the body’s capacity to neutralize them using antioxidants such as glutathione, catalase, and superoxide dismutase.51,53 Elevated ROS levels damage DNA, proteins, and lipid membranes, leading to cellular dysfunction or apoptosis.54-55 In neurodevelopment, this can alter synapse formation, axonal growth, and myelination – processes essential to cognitive and sensory integration.56

Autistic populations have been found to carry multiple genetic polymorphisms in redox-related pathways, including glutathione synthesis (GCLM, GSS), detoxification enzymes (GSTP1, SOD2), and methionine-homocysteine cycling genes (MTHFR, MTRR).57-60 These variants can reduce antioxidant capacity, impair detoxification,61-62 and weaken epigenetic methylation control – a triad that makes the developing brain highly susceptible to harm when environmental stressors are introduced.21,51

4.Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Fatty Acid Oxidation

Mitochondria are the energy-generating organelles within cells; they are also pivotal regulators of apoptosis, calcium buffering, and ROS signalling.63-64 Several studies have identified biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism, including elevated lactate,65 alanine, carnitine deficiency, and impaired electron transport chain activity.66-67

Importantly, mitochondrial function is deeply interwoven with fatty acid oxidation (FAO) – for example, mitochondria β‑oxidize fatty acids via the carnitine shuttle into acetyl‑CoA, feeding the TCA cycle and ETC for ATP.68-69 Disturbances in FAO impair electron transport chain assembly and energy production.70-71

Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) variants are highly pathologised without necessary consideration of environmental context.72 Notably, Auer et al. conferred in their 2015 article that metabolic flexibility maintains a growth advantage under fluctuating food conditions,73 highlighting that certain FAO configurations are likely to be evolutionarily adaptive rather than inherently disordered.

Medium‑Chain Acyl‑Coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Deficiency (MCAD) deficiency or CPT-II deficiency, are defined as disorders of FAO,74 and are rarely diagnosed,72 but contribute significantly to metabolic stress and neurodevelopmental risk when unrecognised.75

The 2024 review by Assaf et al. Unravelling the Evolutionary Diet Mismatch and Its Contribution to the Deterioration of Body Composition reveals that modern diets (high in ultra‑processed foods, low in dietary complexity) create a mismatch with the evolved metabolome, which can undermine metabolic resilience.76An earlier 2020 paper Environmental Influence on Neurodevelopmental Disorders also demonstrates how environmental exposures (nutrition, toxins, inflammation) strongly shape neurodevelopment.77 These articles support the perspective that an FAO variant’s pathological risk depends significantly on the environmental context.

Children with divergent mitochondrial or fatty acid oxidation (FAO) function may be particularly vulnerable to immune-activating events such as febrile illness or vaccination.45,78 In such cases, the associated surge in metabolic demand and inflammatory signalling can exceed mitochondrial reserve capacity,79 leading to neuronal stress, encephalopathy,80-81 or developmental regression.53,82 This mechanism has been observed in subsets of autistic children and confirmed mitochondrial dysfunction, where environmental stressors precipitate regression or seizure activity.83 Case reports, including the well-documented Poling case, underscore this risk in genomically divergent individuals.84

These biochemical profile distinctions – often framed as dysfunctional – are in fact rooted in ancient genetic architectures that shaped divergent human physiology long before modern environmental pressures. To understand this fully, it is necessary to examine the ancestral genomic contributions, including those inherited from Neanderthals, that continue to inform metabolic and neurological variation today.

5.Genomic Ancestry and Lineage

A 2024 study by Pauly et al. identified significant enrichment of specific Neanderthal-derived single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in autistic probands and their siblings.85 This was particularly within Black non-Hispanic, White Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic populations. While resilience is often framed as a psychological trait, its evolutionary roots lie in deep neurobiological adaptations shaped by environmental pressures. Neanderthals demonstrated extraordinary persistence across glacial cycles, maintaining cultural and ecological adaptations over more than 300,000 years.86 This overlaps with known distributions of methylation-related variants such as the MTHFR C677T polymorphism, enriched in autistic populations,87 and supports a convergence between archaic genomic inheritance and modern biochemical (in)tolerance.

Divergent individuals – particularly those carrying MTHFR C677T and related folate-cycle polymorphisms – exhibit differential biological profiles shaped by ancestral genomic inheritance. This includes altered folate processing, mitochondrial signalling, and redox regulation.88-89 These are not defects, but systemically unacknowledged expressions of biological diversity that may become problematic only under environmental mismatch. Neanderthal-introgressed alleles have been linked to structural differences in tracheal branching, thoracic organisation, collagen networks, and midline patterning – traits that develop early in gestation and are tightly regulated by folate-methylation-oxidative pathways.90-92 In the presence of synthetic folic acid, highly processed foods, xenobiotics, or toxic overload, these profiles experience disproportionate strain on developmental and detoxification capacity. These outcomes reflect not a genetic failing, but a systemic failure to accommodate genomic diversity in public health.

The ongoing integration of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans – particularly in genes regulating immunity, neural development, and circadian rhythm – underscores its adaptive significance.93-95 These archaic segments are not randomly inherited; they persist where they offer functional advantage, such as immune responsiveness.96 Many cluster in expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTLs), influencing gene expression in the brain, skin, and immune system.85,94-97 Introgressed variants have been associated with increased sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation, pain perception, and traits like chronotype, attention, and mood regulation.90-92,94-95 Neanderthal alleles are also enriched in synaptic plasticity and cortical development regions that overlap with autistic traits.85,94-97 A comparable case is seen in the EPAS1 variant of Denisovan origin, enhancing hypoxia tolerance in Tibetans – demonstrating how archaic introgression can shape population-specific adaptive physiology.98

New research by Barker et al. also provides essential support for a broader reconceptualization of autistic embodiment as a form of archaic intentional persistence rather than pathology.90 Their study reveals that introgressed Neanderthal variants significantly alter transcription factor (TF) binding across diverse promoter regions. These are located not only in neurodevelopmental genes, but also those affecting mitochondrial metabolism, skeletal morphology, immune regulation, and connective tissue networks. Several of the affected TFs – including FOXP1, and RORA- are already established in autism literature.99-100 These differentially binding TF targets show dynamic expression during prenatal and early postnatal windows – with peak activity in brain regions critical for neurodevelopment. LYRM4 and FARS2 are highlighted by Barker et al. as differentially regulated loci related to oxidative phosphorylation.90 This relays how mitochondrial energy metabolism – a proposed vulnerability axis in autism – is shaped by archaic inheritance. When considered alongside anatomical evidence of atypical collagen structure,26 altered energy regulation,23,49 and distinctive patterns in autistic individuals,78,83,101 this data further supports the view that autism may reflect a polygenic, ancestrally conserved variant of human embodiment.102-103 Likely pathologised due to observable reactions to toxins and environmental stressors.

In their 2021 paper, Findley et al. identified that Neanderthal-derived alleles modulate transcription factor activity in glucose-regulatory systems, providing a compelling genomic clue that inherited metabolic adaptations may underlie modern diet mismatch in divergent populations.104 These expressions of lineage-specific metabolic tuning, shaped by archaic environments, become mismatched in contemporary toxic, synthetic, and overstimulating surroundings.21,46,48-51,54 These findings intersect with broader metabolic signatures in autistic populations, including mitochondrial inefficiency, altered insulin signalling, differential glucose regulation, and an increased prevalence of glycogen storage variants.105

Shin et al.’s 2024 research proposes that rare recessive variants in non-coding regulatory elements – including Human Accelerated Regions (HARs), conserved neural enhancers (CNEs), and validated enhancers (VEs) – contribute to autism ‘risk’, particularly in consanguineous populations.106 Yet their interpretation frames these variants as harmful mutations, overlooking key principles of evolutionary biology and regulatory context.32 HARs, by definition, are regions of rapid human-specific evolution that underwent positive selection.107 If variants within these loci were purely deleterious, they would not persist within the genome or remain enriched near neurodevelopmental regulators. Enhancers such as those in proximity to SIM1 and OTX1 – which regulate hypothalamic signalling, social development, and circadian rhythm – do not simply encode dysfunction but reflect lineage-specific adaptations. Their expression is shaped by environmental state, redox status, and developmental timing.93,97 Shin et al. demonstrated altered enhancer activity using MPRA and CRISPR interference, yet make no attempt to examine whether these effects are context-dependent.106 They present enhancer variants as inherently pathological, rather than conditionally responsive to environmental cues such as toxic exposures, synthetic nutrients, metabolic load, or mitochondrial stress38-39,43,46 mischaracterising the nature of regulatory biology.32,96

Shin et al. also omit discussion on OXTR from OTX1 -linked enhancers in their research.106 OTX1 is a homeobox transcription factor that governs forebrain architecture and the development of hypothalamic structures implicated in affective regulation, while OXTR encodes the oxytocin receptor, which modulates empathy, bonding, and sensory gating.108-109 These systems operate in neurodevelopmental sequence, with divergence in one modulating the dynamics of the other. Omitting OXTR removes the downstream social-affective context from any discussion of OTX1, reinforcing a fragmented and biologically impoverished view of genomic influence. An integrative framework could examine how transcriptional regulators like OTX1 interact with neuroendocrine peptide modulators like OXTR, particularly under conditions of environmental mismatch. Regulatory divergence under these conditions may reflect context-sensitive resilience, and not static risk. To interpret such variants as pre-determined pathology – without considering metabolic overload, redox imbalance, or synthetic exposures – collapses complex gene–environment systems into an oversimplified model.

6.Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels and Vaccine Sensitivity

CACNA1C, which encodes a subunit of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC), has been linked to autism and other neurodevelopmental psychiatric diagnoses due to its role in neuronal signalling and brain connectivity.110

Individuals with specific variants in voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) genes – particularly CACNA1C, CACNA1A, and CACNA1H-may exhibit increased neurophysiological sensitivity to immune activation;111-114 this could include live-virus vaccines such as MMR. VGCCs regulate calcium influx in neurons, immune cells, and cardiac tissue in response to depolarization.115 Excessive calcium entry through L-type VGCCs, especially in those with CACNA1C risk alleles (e.g., rs1006737 A), can result in oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation.110,116-118

In individuals with concurrent vulnerabilities in methylation or antioxidant pathways-such as homozygous MTHFR C677T, COMT Val158Met, or deletions in GSTM1 or SOD2 – the system’s ability to buffer this calcium overload is impaired.119 Immune activation from vaccines is known to raise inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α,120 which are known modulators of VGCC activity and mitochondrial ROS production.121 This cascade may be especially destabilising in neurodevelopmentally sensitive children, where calcium signalling plays a role in synapse formation, plasticity, and circadian rhythm regulation.122-123

Excessive VGCC activation also leads to downstream glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity – a critical mechanism in neuroinflammation and neuronal injury.124 Calcium influx potentiates the release of glutamate, and in genetically sensitive individuals, this can result in chronic neuronal hyperexcitability, impaired pruning, and excitatory/inhibitory imbalance.125 If unmitigated – particularly in the context of poor redox balance due to MTHFR or SOD2 variants – excess glutamate may overstimulate NMDA receptors, leading to mitochondrial collapse and oxidative injury.126 Clinically, this may present as motor tics,127 regression, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and sensory overload82 These are symptoms reported following MMR in children with predisposing genomic profiles.54,67,78,82,84

7.Cumulative Toxic Load: Acetaminophen

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a small, moderately lipophilic molecule that remains largely uncharged at physiological pH, enabling it to readily cross both the placental barrier and the blood-brain barrier.128-129 Studies have demonstrated that following maternal intake, paracetamol enters the foetal circulation at concentrations approximating maternal plasma levels,130 and due to the immaturity of the foetal blood brain barrier it can penetrate the developing central nervous system.131-132

Paracetamol’s antipyretic and analgesic actions rely not on peripheral pathways alone, but critically on central inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis within the CNS.133-134 Specifically, paracetamol reduces PGE2 synthesis in the hypothalamus by inhibiting prostaglandin H2 synthase.135 These prostaglandins are essential not only for pain and temperature regulation but also play roles in neurodevelopment, synaptic plasticity, and microglial function.136

Paracetamol is primarily metabolized in the liver, where a small proportion is converted into a toxic metabolite called N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI).137-138 Under normal conditions, NAPQI is neutralized by glutathione, the body’s master antioxidant. However, genetic variants can affect metabolism,54,60 and this is currently unaccounted for in clinical guidance or practice. When paracetamol is taken repeatedly over time, glutathione stores become further depleted, allowing NAPQI to accumulate. This excess NAPQI can then bind to cellular proteins, leading to oxidative stress,139 mitochondrial dysfunction, and tissue damage, particularly in the liver and possibly in the brain.137 Glutathione depletion is especially concerning in vulnerable populations, including neonates, pregnant women, and genomically divergent populations.

These effects may compound genetic or epigenetic vulnerabilities in susceptible populations, such as those with compromised glutathione pathways,54 mitochondrial variants,66 or neuroimmune sensitivity.78

This section does not suggest that acetaminophen causes ‘autism’ but rather emphasizes toxic burden and its disproportionate effects on divergent genomics. Ongoing research is essential, particularly in light of rising developmental and chronic health problems, and the lack of random controlled trials (RCTs) due to ethical constraints on experimentation during pregnancy.

8.Connective Tissue Vulnerability and the Blood-Brain Barrier

The blood brain barrier is composed of endothelial cells joined by tight junctions, pericytes, and astrocytic end-feet, underpinned by a basement membrane rich in connective tissue proteins, including collagen IV, fibronectin, and laminin.140 Genomic or acquired weaknesses in these structural proteins – especially mutations in COL3A1, COL5A1, and COL6A3, as seen in EDS and related connective tissue differences – can result in vascular fragility and increased paracellular permeability.141-142 Therefore, individuals with such connective tissue variants, which are enriched in divergent populations,26 may be predisposed to impaired blood brain barrier integrity and therefore at increased risk of permeability.

Structural vulnerabilities are compounded by inflammatory and oxidative stressors, which further compromise the blood brain barriers integrity.143 Studies demonstrate that systemic inflammation, histamine release, and oxidative stress can increase tight junction breakdown and transcytosis activity across the blood brain barrier. Notably, individuals with connective tissue disorders frequently exhibit mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) or histaminergic dysregulation, which has also been shown to open the blood brain barrier through histamine-mediated loosening of endothelial junctions.144

Aluminium, a known neurotoxin, is not inherently lipid-soluble and cannot freely cross an intact blood-brain barrier. However, it can form complexes with citrate or transferrin, mimicking physiological ions and gaining entry via carrier-mediated transport and is partially retained in neural tissue.145-148 Reports of elevated aluminium in autistic brains149-150 are consistent with increased uptake under converging conditions of impaired FAO, ECM fragility, and reduced LPC-DHA transport. Aluminium’s neurotoxicity is therefore amplified not by a single defect, but by pre-existing multi -systemic divergence in connectivity and barrier regulation.

The presence of systemic inflammation, vascular permeability, and epithelial breakdown further increases its access to the central nervous system. Animal and human studies have shown that elevated aluminium concentrations in brain tissue are associated with neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions, particularly under conditions of impaired detoxification or barrier function.149-150 This does not assert that neurotoxins cause autism, but rather that autistic populations are disproportionately harmed by them.

Collagen biosynthesis is among the most energy- and redox-intensive processes in the body.74 Hydroxylation of proline and lysine residues requires oxygen, vitamin C, Fe²⁺, and a steady ATP/NAD⁺ supply.151 FAO generates much of this ATP in fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Variants impairing FAO reduce ATP generation, disrupt NAD⁺/NADH balance, and increase oxidative stress.152 When combined with mitochondrial NADH shuttle saturation, as described by Wang et al. in their 2022 study,153 this can drive a compensatory metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis, exacerbating redox stress and cellular dysfunction. Under these conditions, fibroblasts also synthesise weaker collagen fibrils and repair extracellular matrix (ECM) less effectively, predisposing to vascular and connective tissue fragility. This metabolic reprogramming, typically associated with rapidly proliferating cells, may also emerge in neuroimmune contexts where mitochondrial throughput is impaired by genomic susceptibilities or overwhelmed by environmental stressors.21,25,34,38 Such saturation may lead to elevated lactate production,65 redox imbalance,23 and altered neuro-energetics,21 all of which are implicated in neurodevelopmental vulnerability without necessitating a primary genetic defect.18

Conversely, inherited connective tissue differences (e.g., COL4A1/2 variants, hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos phenotypes) destabilise the basement membrane of the BBB and impose chronic ECM repair demands.154-155 This increases cellular energy requirements, unmasking latent FAO inefficiency.156 Therefore, FAO and collagen variants form a positive feedback loop: reduced FAO destabilises collagen, while collagen fragility amplifies FAO stress, together weakening structural barriers against environmental stressors.

Lipid metabolism represents another layer of complexity; the transporter MFSD2A is essential for BBB integrity, ferrying Lys phosphatidylcholine (LPC)-bound docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) into the brain.157-158 DHA incorporation into endothelial membranes suppresses vesicular transcytosis and stabilises the barrier. LPC is derived from phosphatidylcholine (PC), whose synthesis depends on intact methylation (via PEMT/SAMe) or adequate choline supply.159 Variants in MTHFR, MTRR, and related pathways, frequently observed in autistic populations,87 suppress PC production and therefore limit LPC-DHA availability for MFSD2A transport. FAO inefficiency compounds this by reducing long-chain PUFA pools and generating oxidative stress that downregulates lipid transport programs.

Empirical studies confirm enrichment of these differences in the autistic population,26 and distinct acylcarnitine patterns consistent with FAO inefficiency have been documented.66 Autistic individuals also show divergent plasma phospholipid and PUFA profiles,160 concurrent with a high prevalence of hypermobility/EDS phenotypes.161-162 These converge with evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in hEDS,163 establishing overlap between metabolic and connective tissue phenotypes in divergence.

Multiple strands of evidence suggest that fatty-acid oxidation (FAO) inefficiency, connective tissue fragility, and lipid transport deficits converge on the integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). While these domains are typically investigated in isolation,72,26 they are metabolically and structurally interdependent. Their intersection provides a unified explanatory model for the clustering of metabolic, connective, and neurodevelopmental traits observed in autistic and neurodivergent populations, and for their disproportionate vulnerability to immunological intervention toxicants such as aluminium. Given the overlap between the neurodivergent profile and connective tissue disorders,26 this axis may represent a critical – yet underexplored – pathway of environmental vulnerability. The co-occurrence of metabolic,23 mitochondrial,49 and connective tissue differences,26 validates that a subset of the population is epigenetically and structurally vulnerable to neuroinflammation and toxicant accumulation. This includes from vaccine adjuvants or other aluminium-containing exposures.145-146,149-150 This raises ethical concerns about risk stratification, individual susceptibility, and public health policies that fail to account for such vulnerabilities.

9.Vulnerability in SIDS and Autism: A Shared CYP450 Pathway

A 2025 landmark study by Goldman and Chen published in the International Journal of Medical Sciences, performed pharmacogenetic screening on 26 infants who died of SIDS after exposure to medications.164 The results showed that all 26 infants carried at least one gene variant associated with poor or reduced drug metabolism, especially in CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6; over half had two or more such variants.

Importantly, Goldman and Chen conclude that impaired detoxification – due to compromised CYP450 enzyme function – may have contributed significantly to these deaths; especially as the infants were exposed to drugs or chemical agents for which they could not metabolically compensate.164 Simultaneously, multiple studies have shown that these very same CYP450 polymorphisms are overrepresented in autistic individuals. A 2023 paper published in the Journal of Developmental and Behavioural Paediatrics by Goodson et al. demonstrates that CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 variants are significantly enriched in autistic children.165 The authors also noted direct implications for toxic load sensitivity and drug processing impairments. The study confirms that autistic individuals may be especially vulnerable to neurotoxins due to altered or delayed metabolism – resulting in saturated or prolonged exposure – interfering with brain development during critical early periods.

While both the Goldman and Chen and Goodson et al. studies provide valuable insights into CYP gene variants – particularly CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 – their scope is inherently limited by a reductionist approach that treats these genes in isolation.164-165 In reality, genes do not operate independently; they function as part of complex biological cascades.19 They often interact with methylation-related genes such as MTHFR, COMT, and others involved in detoxification, neurodevelopment, and immune regulation. It remains unclear whether additional relevant polymorphisms, such as MTHFR, COMT, GSTM1, or if other genes involved in methylation and detoxification were included in the original genotyping panels used in these studies. Given that such genes are commonly present on standard pharmacogenomic testing platforms, the omission of these variants represents a notable limitation. Inclusion of these markers would have offered a more comprehensive understanding of potential gene-gene interactions and their relevance to neurodevelopmental risk or metabolic vulnerability. As such, the findings, while informative, may capture only a partial view of the broad and interconnected genomic landscape.

One 2021 review by Miller examined 2,605 infant deaths reported to the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) between 1990 and 2019, noting that “58% clustered within 3 days post-vaccination and 78.3% occurred within 7 days”.166 VAERS is often criticised for its passive design – relying on self-reports that are neither routinely verified nor subjected to systematic follow-up – yet, it remains the central mechanism for post-market vaccine surveillance in the United States. Despite decades of such critique, no replacement or parallel system with active monitoring, standardised causality assessment, or long-term outcome tracking has been implemented.

10.Mapping Phenotype Timing to Vaccine and Environmental Exposure Windows

A 2025 Nature Genetics phenotyping paper has attempted to stratify autism into developmental subtypes based on gene expression timing.167 Litman et al. conducted their phenotypic decomposition analysis using data from the SPARK cohort (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge), a large-scale U.S. initiative integrating genomic and clinical data from over 100,000 individuals to advance autism research.168 This review identifies specific age windows – such as 12–18 months or 24–36 months – during which phenotype-defining gene expression patterns emerge. However, while the genetics are explored in depth, epigenetic variables are omitted entirely. Despite presenting over 18,000 genome sequences and assigning subtypes based on mutation clusters, the study fails to explore how environmental interactions may shape phenotypic trajectories.

10.1. Missed Epigenetic Dimensions

Despite acknowledging the critical importance of timing, the SPARK dataset and the 2025 Nature review by Litman et al. fail to account for gene-environment interaction, epigenetic susceptibility, or environmentally modifiable pathways.167-168 This is a critical omission given that the timing of vaccine schedules, weaning, pathogen exposure, and toxicant exposure often coincide with these exact windows of phenotypic emergence. If phenotypes emerge following or during oxidative stress events – such as post vaccination in a child with metabolic vulnerabilities – then it is essential to at least consider that we are observing epigenetically mediated neurodevelopmental outcomes, and not genetically predetermined traits.

For example, if a child presents with regressive traits post-MMR at 15–18 months, and that phenotype aligns with a defined ‘language-regression cluster’ in the study, it must not be concluded that the phenotype is inherent or innate. Accounting for the oxidative load, fever response, and immune/metabolic interplay during that specific window is a key to understanding gene-environment interaction and its effect on observable presentation.

‘Autism’, in the observable diagnostic context, is often understood to emerge from gene-environment interaction, not static mutation alone.169 Studies have demonstrated:

- DNA methylation patterns in children diagnosed as autistic differ significantly from controls, especially in oxidative stress and immune-related genes.170

- Mitochondrial DNA copy number and epigenetic dysregulation correlate with regression events and cognitive decline in susceptible children.21,82

- Exposure to environmental or immune triggers during critical windows can result in epigenetic silencing of neuroprotective genes in those with metabolic vulnerabilities.171

Yet the Nature article by Litman et al. proposes five subtypes of autism rooted solely in inherited variance, without acknowledging that phenotypes can emerge through modifiable cascades.167

It is also important to recognise that environmental interactions do not necessarily arise from a singular event, but from the cumulative effect of multiple factors – some of which exert greater impact than others; this research synthesis focuses solely on the commonly recognised and significant systemic contributors within that broader landscape.

11.The Vaccine Schedule Overlap

The UK childhood vaccination schedules converge critical immunizations – such as MMR, MenB, DTaP/IPV, and PCV – at 2 months, 4 months, 12 months, and 15–18 months.172 These immunological interventions represent acute, non-trivial immune events involving adjuvants (e.g., aluminium salts), preservatives (e.g., polysorbate 80), and inactivated viral material – all capable of triggering oxidative cascades, blood brain barrier permeability, and neuroinflammation in vulnerable populations.173-174

Current regulatory guidance and product information leaflets (PILs) for childhood vaccines, including the widely used Infanrix Hexa (a six-in-one vaccine), contain explicit warnings that the product should not be administered to individuals aged seven years or older. The rationale provided is that older individuals are more likely to experience “severe but transient local and febrile reactions”175 potentially due to heightened immune responsiveness. This disclosure is of significance, as it implies that a stronger or more reactive immune system confers a greater risk of adverse effects following vaccination. Importantly, associated clinical guidelines do not acknowledge that certain younger populations may also possess immune systems that are inherently more reactive. This is particularly relevant to divergent individuals with functional metabolic genomic variants, such as autistic, ADHD, and related diversities.24-25,78

A substantial body of literature now supports the view that neurodivergent populations exhibit heightened immune activation, both systemically and within the central nervous system. Many studies have identified elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ) in autistic individuals,176-177 as well as increased microglial activation in postmortem brain tissue.178 These immune features are not incidental but form part of the underlying biology of neurodevelopmental difference. They are often accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction,21 methylation diversity (e.g., MTHFR polymorphisms),87 and increased blood–brain barrier permeability through connective tissue differences26 – all of which can further exacerbate vulnerability to vaccine-induced neuroinflammation.82,84 Given this, it is inconsistent to state that a vaccine is contraindicated in older children due to enhanced immune reactivity, while failing to recognize that similar immunological reactivity may be present in younger genomically divergent children. 24-25,78 These children are typically subjected to the full vaccination schedule during their most neurologically sensitive developmental window.44,172

This represents a fundamental failure in the risk stratification model currently employed in vaccination policy. It assumes a uniform safety profile across all children under seven, despite mounting evidence that biological heterogeneity-particularly within the neurodivergent population-confers a materially different risk profile.

12.The Epigenetic Timeline

A striking temporal overlap is observed when mapped against the phenotypic expression windows identified in the 2025 Nature article by Litman et al.167 For instance:

- The early sensory subtype is associated with developmental changes from 6–12 months – coinciding with MenB and DTaP booster doses.167,172

- The language and social regression subtypes emerge at 15–18 months – coinciding with the MMR vaccine and PCV booster.167,172

- The motor coordination subtype shows disruption at 24–30 months – a period often following the full primary schedule and multiple inflammatory events.167,172

A 2017 longitudinal analysis of typical children by Xu et al. demonstrated that CpG sites undergo methylation changes from birth to age 8, but that these changes are distributed and progressive, reflecting standard tissue maturation and immune development.179

Abrupt epigenetic shifts are observed only in contexts of physiological stress or injury. For example, a 2024 preterm infants’ study by Hodge et al. displayed a large cohort of differentially methylated regions at NICU discharge – many involving immune, inflammatory, and neurological pathways.180 These changes reflect response to systemic stress, not planned developmental programming.

The phenotypic classes in the Litman et al. study and SPARK dataset are associated with condensed timing windows of gene expression,167-168 often coinciding with known stress exposures such as toxins, immune activation, and rapid postnatal synaptogenesis.172 Without accounting for epigenetic mechanisms, the interpretation of this expression data remains incomplete.

These findings implicate that:

- Neurotypical development involves gradual, diffuse epigenetic adaptation.179

- Stress or injury induces localized, high-impact epigenetic disruption.180

- The timing and intensity of gene shifts in profound autistic subtypes more closely resemble a stress signature than a passive genomic trajectory.21,82

This comparative evidence strengthens the hypothesis that environmental triggers77 -when introduced during key developmental windows – can drive epigenetic dysregulation in susceptible children,34-35,38 resulting in regression or developmental derailment.21,28 These effects are therefore not innate, but disruption layered upon a genomically divergent foundation.

The Nature review by Litman et al.167 had the potential to be revolutionary, if the original SPARK dataset168 had included:

- Epigenetic methylation profiling.

- Immune and mitochondrial biomarkers.

- Exposure histories.

With those variables documented, the Litman et al. study may have identified why one child with SHANK3 remains stable, while another with identical variants regresses into profound disability after immune activation. Whereas, the failure to include epigenetic mechanisms, gives the illusion that observable phenotypes are purely innate, when they are most accurately described as preventable gene-environment outcomes.169,181

13.Gene-Environment Interaction and Epigenetic Injury

Key genes implicated in autism – such as SHANK3, SCN2A, MECP2, CHD8, and SYNGAP1 – are known to interact with epigenetic modifiers and respond to redox imbalance.43,169,181 SHANK3, for instance, is sensitive to oxidative stress and regulates glutamate receptor function, while MECP2 is a methyl-binding protein central to chromatin regulation and neuroplasticity. These genes do not operate in isolation but within regulatory networks that can be epigenetically modified by environmental signals.19,43

Studies have shown that perinatal exposure to immune challenges (e.g., maternal infection), toxins (e.g., air pollution, heavy metals), and pharmaceuticals (e.g., valproate) can trigger long-lasting changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation, particularly in the frontal cortex and cerebellum – regions crucial to executive function and sensorimotor integration.182-184

These findings underscore that the ‘autism’ diagnosis does not reflect a singular static condition but an interplay of genetic baseline and dynamic epigenetic modulation, heavily influenced by redox status, immune signalling, and mitochondrial capacity. In children with genetic vulnerabilities – including those with FAO disorders, methylation SNPs, or mitochondrial fragility – the risk of developmental derailment increases sharply when environmental stressors coincide with sensitive neurodevelopmental windows.44

14.Gene Clusters and Modifiability

This paper proposes and outlines a two-tiered model:

The genes identified within these proposed phenotypes include both static and modifiable types.

For example:

- Static: SCN2A, CHD8, and SHANK3 – high-penetrance genes often present in congenital autism. These may include genes like CNTNAP2, NRXN1, or CHD8, known to shape neural architecture from early development.185-186

- Epigenetically Modifiable: SLC25A12, MTHFR, GCLM, and GSTP1 – Genes involved in detoxification (e.g., GSTM1), methylation (e.g., MTHFR, BHMT), mitochondrial function (e.g., NDUFS4, POLG), and immune regulation (e.g., HLA, TNFα) are more responsive to environmental stressors. These may remain silent or harmless until triggered and their expression is shaped by redox state, inflammation, and methylation availability48,185-186,187-188

The interaction between these two tiers – one structural, one modifiable – determines both neurodivergent baseline traits and susceptibility to neurodevelopmental injury.

Notably, children with both static and modifiable gene combinations tend to exhibit the most neurologically impacted phenotypes in the Litman et al. review,167 supporting the theory that regressive autism is often a disturbance-on-genomic divergence model. This is similar to the two-hit hypothesis widely accepted in neurodevelopmental science.

15.The Two-Stage Hypothesis and the Divergent-Metabolic Interface

The convergence of genetic vulnerability and environmental stressor as a causal model of neurodevelopmental harm is not a novel idea, but it has rarely been applied systematically to autism. The well-documented two-hit hypothesis, originating in cancer biology and later applied to neuropsychiatry,189-190 provides a conceivable framework through which regressive autism and vaccine-induced injury can be understood – not as anti-scientific conjecture, but as grounded biological plausibility. This hypothesis suggests that genetic susceptibility establishes a differential response biological terrain, and environmental triggers act as the ‘hit’ that initiates or accelerates neurodevelopmental derailment. This is particularly evident in cases where children appear to lose language, social engagement, or motor skills quickly following illness or medical intervention.82,84 In such cases, the timing of the stressor intersects critically with the child’s metabolic bandwidth – that is, their genetically determined capacity to detoxify, repair, and regulate neuroimmune signals.

15.1 Divergent Genomics and Autism as a Genetic Vulnerability

Demographics with divergent genomics represent an unaccounted-for framework: a foundation of inherent variants, often accompanied with biological differences – including static gene variants (e.g., SHANK3, CHD8, NRXN1).185-186 These genes predispose individuals to hidden developmental uniqueness; neurologically,22 biologically23 and also physiologically26.

However, when these static variants coexist with dynamic, environmentally modifiable genes – particularly those involved in redox balance, methylation, detoxification, and mitochondrial function – a significantly compromised terrain is formed. Examples include:

- MTHFR C677T / A1298C: Affects folate metabolism and methylation capacity.48,87

- SLC25A12: Implicated in mitochondrial energy metabolism and excitatory signalling.188,191

- GCLM and GCLC: Rate-limiting enzymes for glutathione synthesis, central to detoxification.54,192

- GSTP1 and GSTM1: Detox enzymes modulated by oxidative burden.60,193

These are not rare genes; many divergent individuals carry multiple such variants18 – usually without awareness, due to lack of screening.

15.2 Stage two: Oxidative Load and Neuroinflammatory Response

When a divergent child reacts to a vaccine (or is exposed to another inflammatory trigger like antibiotics, high fever, or pollutants), the environmental ‘hit’ occurs. This does not cause autism, as such – but it may cause neurodevelopmental regression, particularly when coinciding with critical windows of brain development (1–3 years of age).

The biological pathway is clear and well-supported:

1. Immune Activation: Vaccines stimulate innate and adaptive immune responses, including cytokine release and fever. Abnormal Cytokine levels in circulating blood are reported in autism.194

2. Oxidative Stress: Children with compromised redox genes are less able to neutralize ROS, leading to sustained inflammation.21,23,48,53,57

3. Mitochondrial Impairment: In genetically predisposed children, mitochondrial efficiency drops under inflammatory stress.45,49,51,65-66

4. Blood brain barrier Permeability: Inflammation increases blood-brain barrier permeability, allowing peripheral immune signals to reach CNS tissue.141,143,146,195

5. Microglial Activation and Synaptic Dysregulation: Resulting neuroinflammation impairs pruning and connectivity.196

This cascade does not necessarily require a pathogen, only a sufficient immune activation event.

Therefore, when a child with functionally divergent genomics is exposed to oxidative stressors – such as medical or immune prompting interventions, anaesthetics, or maternal inflammation – epigenetically responsive genes may:

- Become silenced (e.g., glutathione synthesis genes).38,43,48

- Become overexpressed (e.g., pro-inflammatory cytokines).45,194

- Or undergo methylation-driven transcriptional disruption, causing mitochondrial collapse, demyelination, and synaptic dysfunction.21-23,49,51

In these cases, regression is not ‘de novo autism’, but a compounded state: the child is genomically divergent and additionally harmed. Their inherent traits are complicated; potentially biologically destabilized and developmental and observable neurological related difficulties emerge.

This does not imply that every divergent child will experience an adverse reaction to vaccination or immune event. Rather, specific functional genomic profiles -particularly those governing mitochondrial resilience, neuroimmune regulation, and cellular stress recovery – confer increased sensitivity to systemic environmental and immunological interventions. These variants are not inherently pathological but may interact unfavourably with environmental stressors, resulting in disproportionate levels of harm for those subgroups.

16.Mapping the Genetic Evidence – Static vs. Modifiable Variants and Phenotypes

Understanding the interplay between static (inherent) and modifiable (epigenetically active) gene variants is central to explaining autism heterogeneity, regressive events, and the disability spectrum. While much of autism research focuses on extremely rare de novo or high-impact mutations, this section highlights polygenic load, systems-level gene interaction, and environmental sensitivity – providing a more integrated biological picture.

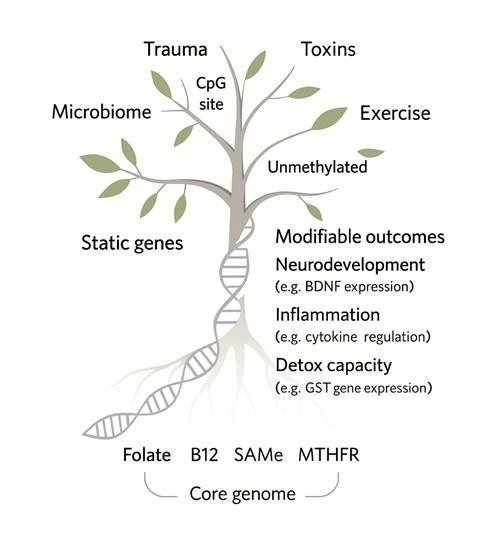

A helpful metaphor is the genetic balance of expression tree (figure 1 page 37): static genes form the trunk – the foundational divergent architecture – while modifiable genes form the branches, influenced by environmental wind. The more branches (variants upon existing variants), the more environmentally sensitive and complex the structure.

Figure 1 above illustrates how factors such as trauma, toxins, and microbial influence may interact with CpG sites and core methylation substrates (e.g. folate, B112, SAMe) to influence modifiable outcomes like neurodevelopment, inflammation, and detoxification197-199

Epigenetic regulation at CpG islands is known to be responsive to environmental stimuli, with studies showing early life stress, toxic exposures, and exercise all impacting gene expression via methylation status.200-202

Key pathways affected include BDNF-linked neurodevelopment,203 cytokine-mediated inflammation,204 and glutathione-related detoxification (e.g. GST polymorphisms).205

This framework reconciles why:

- Some autistic or divergent children regress developmentally post-vaccine while others do not.

- Regression timing coincides with vaccine schedules.

- Developmentally affected children are later diagnosed as autistic or carry neurodivergent genetic markers.

16.1 Static Genes: Core Architecture

These are non-environmentally modifiable genetic variants that form the biological basis of core autistic traits – such as sensory processing differences, pattern-driven cognition, and social-communicative development. Static genes are often involved in synaptic structure, neuronal migration, and early brain patterning, including:

- SHANK3 – synaptic scaffolding protein, crucial in excitatory/inhibitory balance.206

- CHD8 – chromatin remodelling gene strongly associated with macrocephaly and high autistic trait burden.207

- SCN2A – sodium channel gene involved in neural excitability, epilepsy–autism interface.208

- NRXN1 / NLGN3/4 – synapse adhesion molecules impacting synaptogenesis and plasticity.209

These variants often appear in diagnostically ambiguous individuals, and may not cause observable disability or traits of neurodivergence in early infancy. They are akin to the core trunk of the tree, shaping fundamental neurodevelopmental architecture.

The phenotype framing also raises significant epistemological and ethical concerns regarding current diagnostic practices. The prevailing diagnostic model is implicitly structured around an architecture-plus-disruption framework, in which underlying genomic divergence is not clinically acknowledged unless it manifests through observable dysfunction. In this view, the phenotype becomes the primary basis for diagnosis, regardless of whether that phenotype reflects an inherent developmental trajectory or the downstream effects of epigenetic modulation following preventable systemic harm. Consequently, traits arising from gene-environment interactions – including those shaped by toxic exposures, iatrogenic factors, or contextual mismatch – are routinely misclassified as intrinsic features of the individual. This conflation not only distorts biological interpretation but risks formalising environmentally induced injury as fixed identity. When phenotypic outcomes shaped by modifiable exposures are codified into diagnostic subtypes, the result is a pathologisation of adaptation rather than an interrogation of causality. Such practices obscure the role of external contributors to functional disruption and raise serious questions about the moral validity of assigning stable diagnostic labels to phenotypes that may, in fact, represent preventable forms of harm.

This papers reframing highlights the fact that many divergent individuals carry structural or genomic differences associated with neurodevelopmental conditions, yet remain undiagnosed due to the absence of overt dysfunction.207,210 In doing so, it redefines divergence as disorder only when it collides with environmental expectations or fails to perform within normative thresholds.211 As such, the framework not only underestimates the scope of biological variation but also shifts attention away from external stressors and systemic incompatibilities that contribute to downstream harm.

16.2 Modifiable Variants: The Epigenetic Interface

In contrast, modifiable variants influence detoxification, mitochondrial function, methylation, and redox buffering; therefore, determining the threshold of environmental tolerance. These variants can be epigenetically silenced or activated depending on exposure. Key examples include:

- MTHFR C677T/A1298C – reduces methylation and folate conversion; associated with increased incidence of autism and vaccine adverse events.48,87

- COMT Val158Met – affects dopamine metabolism, stress resilience, and oxidative burden.212

- GCLM/GCLC – glutathione synthesis genes critical in detoxifying vaccine adjuvants.213-214

- SOD2, CAT, GPX1 – antioxidant enzymes whose SNPs reduce ROS buffering under immune stress.23

- SLC25A12 – mitochondrial transporter gene overexpressed in ASD, linked to energy metabolism defects.191

Metaphorically, these genes are the branches of the tree – responsive to wind (exposure), variable in expression, and central to environmental vulnerability.

The neurodevelopmental tree metaphor introduced in this paper – with static genes forming the trunk and modifiable SNPs as the branching architecture – also has significant implications for understanding the synaptic pruning hypothesis in autism. Traditionally, autism has been associated with an excess of synapses and a presumed failure of pruning.215 However, this may reflect not dysfunction, but increased genetic and metabolic branching capacity. In a system with expanded SNP expression and regulatory complexity, greater synaptic density may be a direct result of that heightened branching – an evolutionary feature, not a flaw. Environmental stressors such as oxidative damage, immune activation, or toxic exposures may then cause entropic overload on this more complex system, manifesting as cognitive, motor, or sensory challenges.

In this model, the pruning narrative must be revisited. The appearance of excess may in fact be adaptive potential, destabilized only by postnatal environmental stress, not defective neurobiology.

17.Conclusion: An integrated Science-Based Understanding

When the question “what causes autism?” is asked, it reflects a categorical misunderstanding. The assumption of causation implies pathology, yet divergence is not caused – it is innate. It arises from ancestral, functionally derived genomic variation that has been evolutionarily conserved for its adaptive, cognitive, and social significance. “Autism” is therefore not an aetiological entity, but a label retrospectively applied to naturally evolved forms of human variation; it is not caused by medical or environmental interventions. However, individuals with divergent genomic profiles are disproportionately harmed by such exposures, including pharmaceutical and systemic stressors. These outcomes are often misclassified, collapsing systemic harm with inherent autistic identity. This reframing erases true divergence, obscures preventable harm, and conflates identity with acquired harm in ways that distort both science and ethics.

The contemporary scientific paradigm remains hindered by reductive binaries and a lack of integrative analysis. Despite a growing body of literature across diverse fields, the failure to synthesise findings has led to persistent blind spots with tangible societal consequences. This fragmentation not only impedes progress but also reinforces systemic misunderstandings and misapplications. There is a pressing need for a more holistic approach – one that embraces complexity, contextual nuance, and cross-disciplinary synthesis. Advancing such a paradigm requires structural reform in the methodologies, frameworks, and incentives that govern scientific research and its translation into practice.

The increasing ability to identify evolutionarily-conserved neurodevelopmental architectures risks being misused to justify their elimination. This is not due to intrinsic dysfunction, but due to their potential impact on industry through heightened sensitivity to systemic and environmental stressors. In this framing, inherited divergence is pathologised not for its nature, but for its incompatibility with a system that harms it.

This reframing has serious consequences. As phenotype stratification efforts expand, there is a growing institutional tendency to normalise the profoundly disabled presentation of autism without investigating the internal processes that shape it. The failure to account for gene-environment interaction, developmental timing, and systemic sensitivity allows preventable harm to be rebranded as natural variation – thereby shielding medical, pharmaceutical, and regulatory systems from accountability. The autistic phenotype, in this proposed model, is not reducible to fixed genetic fate; it is the emergent outcome of systemic interaction – and must be understood, supported, and protected as such.

We are inadvertently preserving genomic resilience, whilst suppressing evolution. In a systematically toxic and incompatible industrial environment, adaptive traits become liabilities, and divergence is forced into retreat. Evolutionary advantage is derailed into dysfunction, and reassigned as disorder. This is not just a crisis for the divergent – it is a crisis for the species. This reframing is not only necessary, it is urgent.

References

1.American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2013. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

2.Waterhouse L. ASD validity. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2016; 3:302–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-016-0085-x

3.Waterhouse L, London E, Gillberg C. The ASD diagnosis has blocked the discovery of valid biological variation in neurodevelopmental social impairment. Autism Res. 2017; Jul;10(7):1182. doi: 10.1002/aur.1832

4.Koi P. Genetics on the neurodiversity spectrum: Genetic, phenotypic and endophenotypic continua in autism and ADHD. Stud Hist Philos Sci A. 2021; 89:52–62. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2021.07.006

5.Waterhouse L. Heterogeneity thwarts autism explanatory power: A proposal for endophenotypes. Front Psychiatry. 2022; Dec 1; 13:947653. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.947653

6.Waterhouse L, Mottron L. Editorial: Is autism a biological entity? Front Psychiatry. 2023; May 2; 14:1180981. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1180981

7.Modabbernia A, Velthorst E, Reichenberg A. Environmental risk factors for autism: An evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Mol Autism. 2017; 8:13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0121-4

8.Persico AM, Bourgeron T. Searching for ways out of the autism maze: Genetic, epigenetic and environmental clues. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(7):349–58. Doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.010

9.Cruz Puerto M, Sandín Vázquez M. Understanding heterogeneity within autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Adv Autism. 2024; Nov 20;10(4):314–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-12-2023-0072

10.Mottron L, Bzdok D. Autism spectrum heterogeneity: Fact or artifact? Mol Psych. 2020 Dec;25(12):3178–85.doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0748-y

11.Bleuler, Eugen. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York, USA: International Universities Press. 1911. [cited October 02 2025] Available from: https://philarchive.org/rec/BLEDPO-2

12.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2(3):217–50. [cited October 02 2025] Available from: https://bpb-us e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.uoregon.edu/dist/d/16656/files/2018/11/Kanner-Autistic-Disturbances-of-Affective-Contact-1943-vooiwn.pdf

13.Asperger H. Die “Autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter [‘The Autistic Psychopaths’ in Childhood]. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1944; 117:76–136. doi:

14.Czech H. Hans Asperger, National Socialism, and “race hygiene” in Nazi-era Vienna. Mol Autism. 2018;9(1):1–43. doi:

15.Rosen NE, Lord C, Volkmar FR. The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5 and Beyond. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021; Dec;51(12):4253-4270. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-04904-1.

16.Verhoeff B. What is this thing called autism? A critical analysis of the tenacious search for autism’s essence. BioSocieties. 2012;7(4):410–32. doi:. https://doi.org/10.1057/biosoc.2012.23

17.Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, Hultman CM, Larsson H, Reichenberg A. The heritability of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1182–4. doi:. 10.1001/jama.2017.12141

18.Gaugler T, Klei L, Sanders SJ, Bodea CA, Goldberg AP, Lee AB, et al. Most genetic risk for autism resides with common variation. Nat Genet. 2014;46(8):881–5. doi:. 10.1038/ng.3039

19.Grove J, Ripke S, Als TD, Mattheisen M, Walters RK, Won H, et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019; 51:431–44. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8

20.Gogate A, Kaur K, Khalil R, et al. The genetic landscape of autism spectrum disorder in an ancestrally diverse cohort. npj Genom Med. 2024; 9:62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-024-00444-6

21.Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Evidence linking oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation in the brain of individuals with autism. Front Physiol. 2014; Apr 22; 5:150. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2014.00150

22.Benkarim, O., Paquola, C., Park, B. yong, Hong, S. J., Royer, J., Vos de Wael, R., C. Bernhardt, B. Connectivity alterations in autism reflect functional idiosyncrasy. Communications Biology, 2021; 4(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02572-6

23.Frye RE, DeLaTorre R, Taylor H, et al. Redox metabolism abnormalities in autistic children associated with mitochondrial disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3: e273. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2013.51

24.Fang, C., Sun, Y., Fan, C. et al. The relationship of immune cells with autism spectrum disorder: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. BMC Psychiatry. 2024; 24, 477. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05927-5

25. Arenella M, Fanelli G, Kiemeney LA, McAlonan G, Murphy DG, Bralten J. Genetic relationship between the immune system and autism. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2023; Dec; 34:100698. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100698

26.Zoccante, L.; Di Gennaro, G.; Rigotti, E.; Ciceri, M.L.; Sbarbati, A.; Zaffanello, M. Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Connective Tissue-Related Symptoms: An Exploratory Case-Control Study in Children. Children. 2025; 12, 33. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010033

27.Mouat JS, LaSalle JM. The promise of DNA methylation in understanding multigenerational factors in autism spectrum disorders. Front Genet. 2022; 13:831221. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.831221

28.Herrera ML, Paraíso-Luna J, Bustos-Martínez I, Barco Á. Targeting epigenetic dysregulation in autism spectrum disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2024; Nov;30(11):1028-1046. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2024.06.004

29.Tick B, Bolton P, Happé F, Rutter M, Rijsdijk F. Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis of twin studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; May;57(5):585-95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12499

30.Fu X, Wang Y, Li L, Cai H, Zhang X, Yao Z et al Decomposing Neuroanatomical Heterogeneity of Autism Spectrum Disorder Across Different Developmental Stages Using Morphological Multiplex Network Model,” in IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems. vol. 11, no. 5; 2024; pp. 6557-6567. doi: 10.1109/TCSS.2024.3411113

31.Abrahams BS, Arking DE, Campbell DB, Mefford HC, Morrow EM, Weiss LA, Menashe I, Wadkins T, Banerjee-Basu S, Packer A. SFARI Gene 2.0: a community-driven knowledgebase for the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Mol Autism. 2013; Oct 3;4(1):36. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-36

32.Zhang J. What Has Genomics Taught an Evolutionary Biologist? Mol Biol Evol. 2023;40(10): msad226. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2023.01.005

33.Kuodza G, Kawai R, LaSalle JM. Intercontinental insights into autism spectrum disorder: a synthesis of environmental influences and DNA methylation. Environ Epigenet. 2024;10(1): dvae023. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eep/dvae023

34. Khogeer AA, AboMansour IS, Mohammed DA. The role of genetics, epigenetics, and the environment in ASD: a mini review. Epigenomes. 2022; Jun 19;6(2):15. doi: 10.3390/epigenomes6020015

35.Garcia-Salinas, O.I., Hwang, S., Huang, Q.Q. et al. The impact of ancestral, genetic, and environmental influences on germline de novo mutation rates and spectra. Nat Commun. 2025; 16, 4527. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59750-x

36.Zietsch, B.P. Genomic findings and their implications for the evolutionary social sciences, Evolution and Human Behavior, Volume 45, Issue 4, 2024; 106596,

ISSN 1090-5138. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2024.106596

37. M. Kardos, E.E. Armstrong, S.W. Fitzpatrick, S. Hauser, P.W. Hedrick, J.M. Miller, D.A. Tallmon, & W.C. Funk, The crucial role of genome-wide genetic variation in conservation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021; 118 (48) e2104642118. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104642118

38.Deth R, Muratore C, Benzecry J, Power-Charnitsky VA, Waly M. How environmental and genetic factors combine to cause autism: A redox/methylation hypothesis. Neurotoxicology. 2008; Jan;29(1):190-201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.09.010

39.Marczylo, E. L., Jacobs, M. N., & Gant, T. W. Environmentally induced epigenetic toxicity: potential public health concerns. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2016; 46(8), 676–700. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408444.2016.1175417

40.Lea A, Subramaniam M, Ko A, Lehtimäki T, Raitoharju E, Kähönen M, et al. Genetic and environmental perturbations lead to regulatory decoherence. eLife. 2019;8: e40538. doi: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.40538.001

41. Agashe D, Sane, M and Singhal, S. Revisiting the role of genetic variation in adaptation. Am Nat. 2023;202(6):704–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/726012

42.Ørsted M, Hoffmann AA, Sverrisdóttir E, Nielsen KL, Kristensen TN. Genomic variation predicts adaptive evolutionary responses better than population bottleneck history. PLoS Genet. 2019; 15(6): e1008205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008205

43.LaSalle JM. Epigenomic strategies at the interface of genetic and environmental risk factors for autism. J Hum Genet. 2013; Jul;58(7):396-401. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2013.49

44. Nelson CA 3rd, Gabard‑Durnam LJ. Early adversity and critical periods: neurodevelopmental consequences of violating the expectable environment. Trends Neurosci. 2020; Jul;43(7):300–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.01.002

45.Frye RE. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Unique Abnormalities and Targeted Treatments. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2020; Oct; 35:100829. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2020.100829

46.Love, C., Sominsky, L., O’Hely, M. et al. Prenatal environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder and their potential mechanisms. BMC Med. 2024; 22, 393. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03617-3

47.Kalkbrenner AE, Schmidt RJ, Penlesky AC. Environmental chemical exposures and autism spectrum disorders: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014; Nov;44(10):277-318. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.06.001

48.James SJ, Cutler P, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, Janak L, Gaylor DW, Neubrander JA. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004; Dec;80(6):1611-7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1611

49.Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012; Mar;17(3):290-314. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.136

50. Usui, N., Kobayashi, H., & Shimada, S. Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5487. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065487

51.Rose S, Frye RE, Slattery J, Wynne R, Tippett M, Pavliv O, et al. Oxidative Stress Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction in a Subset of Autism Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines in a Well-Matched Case Control Cohort. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9(1): e85436. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085436

52.Chauhan A, Chauhan V, Brown WT, Cohen I. Oxidative stress in autism: increased lipid peroxidation and reduced serum levels of ceruloplasmin and transferrin–the antioxidant proteins. Life Sci. 2004; Oct 8;75(21):2539-49. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.038

53.Rose, Shannon, Melnyk, Stepan, Trusty, TimothyA., Pavliv, Oleksandra, Seidel, Lisa, Li, Jingyun, Nick, Todd, James, S. Jill, Intracellular and Extracellular Redox Status and Free Radical Generation in Primary Immune Cells from Children with Autism, Autism Res Treat. 2012; 986519, 10 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/986519

54.Rose S, Melnyk S, Pavliv O, Bai S, Nick TG, Frye RE, James SJ. Evidence of oxidative damage and inflammation associated with low glutathione redox status in the autism brain. Transl Psychiatry. 2012; Jul 10;2(7): e134. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.61

55.Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways

by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016; Dec;1863(12):2977-2992. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012

56.Liu X, Zhang Y, Ma P, et al. Roles of neuroligins in central nervous system development. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):362. doi:10.1186/s12967‑022‑03625‑y

57.James SJ, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, Cleves MA, Halsted CH, Wong DH, Cutler P, Bock K, Boris M, Bradstreet JJ, Baker SM, Gaylor DW. Metabolic endophenotype and related genotypes are associated with oxidative stress in children with autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006; Dec 5;141B (8):947-56. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30366

58.Tisato V, Silva JA, Longo G, Gallo I, Singh AV, Milani D, Gemmati D. Genetics and Epigenetics of One-Carbon Metabolism Pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Sex-Specific Brain Epigenome? Genes. 2021; 12(5):782. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050782

59.Rahmani, Z., Fayyazi Bordbar, M.R., Dibaj, M. et al. Genetic and molecular biology of autism spectrum disorder among Middle East population: a review. Hum Genomics. 2021; 15, 17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-021-00319-2

60.Rahbar MH, Samms-Vaughan M, Kim S, Saroukhani S, Bressler J, Hessabi M, Grove ML, Shakspeare-Pellington S, Loveland KA. Detoxification Role of Metabolic Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Genes in Blood Lead Concentrations of Jamaican Children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Genes. 2022; 13(6):975. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13060975

61.Hannon E, Gorrie-Stone TJ, Smart MC, Burrage J, Hughes A, Bao Y, et al. Leveraging DNA-methylation quantitative-trait loci to characterize the relationship between methylomic variation, gene expression, and complex traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2018; Nov 1;103(5):654–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.09.007

62.Aronica L, Ordovas JM, Volkov A, Lamb JJ, Stone PM, Minich D, et al. Genetic biomarkers of metabolic detoxification for personalized lifestyle medicine. Nutrients. 2022; Feb 11;14(4):768. doi: 10.3390/nu14040768

63.Zong, Y., Li, H., Liao, P. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024; 9, 124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01839-8

64.Baev AY, Vinokurov AY, Novikova IN, Dremin VV, Potapova EV, Abramov AY. Interaction of Mitochondrial Calcium and ROS in Neurodegeneration. Cells. 2022; Feb 17;11(4):706. doi: 10.3390/cells11040706