© Alexandra Chambers | Neurotopia CIC | January 2026

During my first pregnancy, the foetus remained in breech position throughout. As I approached term, NHS clinicians became increasingly insistent on scheduling an external cephalic version (ECV) – a manual procedure to turn the baby into a head-down position. I declined because I had a deep, embodied intuition that it wasn’t safe. Despite wanting a natural birth, I knew – without being able to explain – that my body wasn’t suited to this intervention. I experienced escalating pressure, including an text from a doctor outside clinic hours, asking me to reconsider. At one point, my heart rate rose during the consultation due to distress, and only then was the procedure called off. Yet no one ever asked why I felt unsafe. No one questioned whether the breech presentation might have a physiological basis.

All female births in my genetic lineage were breech presentation, and so I knew there must be a fundamental reason.

I didn’t know I was neurodivergent back then and I certainly didn’t know about divergent biology like I do now.

Crucially, no professional actually mentioned the shape of my uterus, despite all the scans I had.

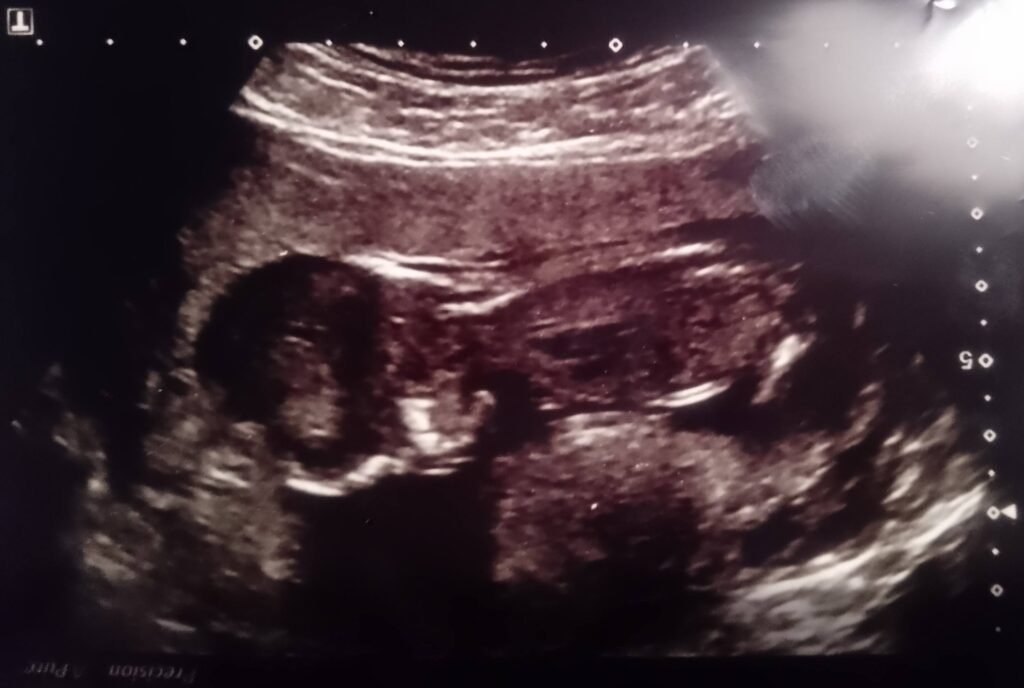

Years later, while reviewing my own archived ultrasound scans, I found what had been missed – or unacknowledged – in real time:

A clear bicornuate or septate uterus.

Across multiple NHS scans, the uterine contour is visibly divided, with implantation restricted to one horn and a second chamber vacant.

Congenital uterine anomalies like this are strongly associated with miscarriage, persistent breech presentation, and altered implantation dynamics. There is also lower ECV success rates – with increased risk of rupture or procedural failure. They are visible using standard 2D ultrasound, which makes their omission from clinical records a critical oversight. In my case, that oversight nearly resulted in an unnecessary and potentially harmful intervention – one that my body instinctively resisted.

This is not just about one anomaly, or one missed diagnosis. I do not have a standard physiology. I carry known genomic variants affecting connective tissue, methylation, and neurobiological regulation. These shape how pregnancy progresses, how the uterus forms and functions, and how the nervous system responds to pressure and intervention.

However, none of that was modelled. I was treated as interchangeable with a clinical average – an average I have never fit. This is what standardised maternity care does to divergent bodies: it fails to see them, fails to ask, and fails to adapt.

![]() My experience is likely not unique. It is simply typical of what goes unspoken in systems that prioritise protocol over physiology.

My experience is likely not unique. It is simply typical of what goes unspoken in systems that prioritise protocol over physiology.

At Neurotopia, I hold space for these truths and recognise that divergence is not pathology – it is a form of biological variation that carries both complexity and legitimacy. Until medical systems are redesigned to model this variation, stories like mine will continue – not as exceptions, but as evidence.

![]() Why Is Only One Uterine Horn Occupied?

Why Is Only One Uterine Horn Occupied?

In a bicornuate or septate uterus, the womb is divided into two chambers – often referred to as “horns.” This split occurs during foetal development, when the two halves of the uterus (Müllerian ducts) do not fully fuse. The result is a uterus with two distinct cavities, separated by a ridge or wall.

During pregnancy, only one horn carries the foetus and the other remains empty.

![]() Ovulation Determines the Side

Ovulation Determines the Side

In each menstrual cycle, only one ovary typically releases an egg. That egg travels down the fallopian tube on the same side, entering just one horn. If fertilisation occurs, implantation happens in that same horn – the embryo cannot cross over to the other side.

One horn becomes active – the other doesn’t.

Once implantation occurs, the pregnant horn becomes hormonally and structurally active:

Its lining thickens.

Blood flow increases.

Uterine muscle tone adapts to support gestation.

Meanwhile, the other horn becomes functionally dormant for the remainder of the pregnancy.

![]() Not all Horns are Equal

Not all Horns are Equal

Even if both horns are structurally present, they’re not always symmetrical in function. One may be better supplied with blood, more spacious, or more receptive to implantation. Some horns may be too small or fibrotic to sustain a pregnancy at all.

The images here show a pregnancy confined to one horn – the other visibly empty.

This is common in bicornuate and septate uteruses, yet rarely acknowledged unless complications arise.

Everything is rare if you refuse to see it.

I have been a bit vulnerable sharing this ![]()

I’m interested to know if there are any similar incidences or divergent biology stories ![]()

![]() – Neurotopia CIC 2026

– Neurotopia CIC 2026

#neurodivergent#neurodiversity#divergent#pregnancy#science#biology#birth#pregnancy#systemsthinking#maternity#inclusionmatters#connectivetissue#Ultrasound#bicornuate#uterus