©Alexandra Chambers | Neurotopia CIC | December 2025

All research is available for PDF digital download on: https://studio.buymeacoffee.com/extras and all money goes directly to Neurotopia CIC to fund further research, thank you.

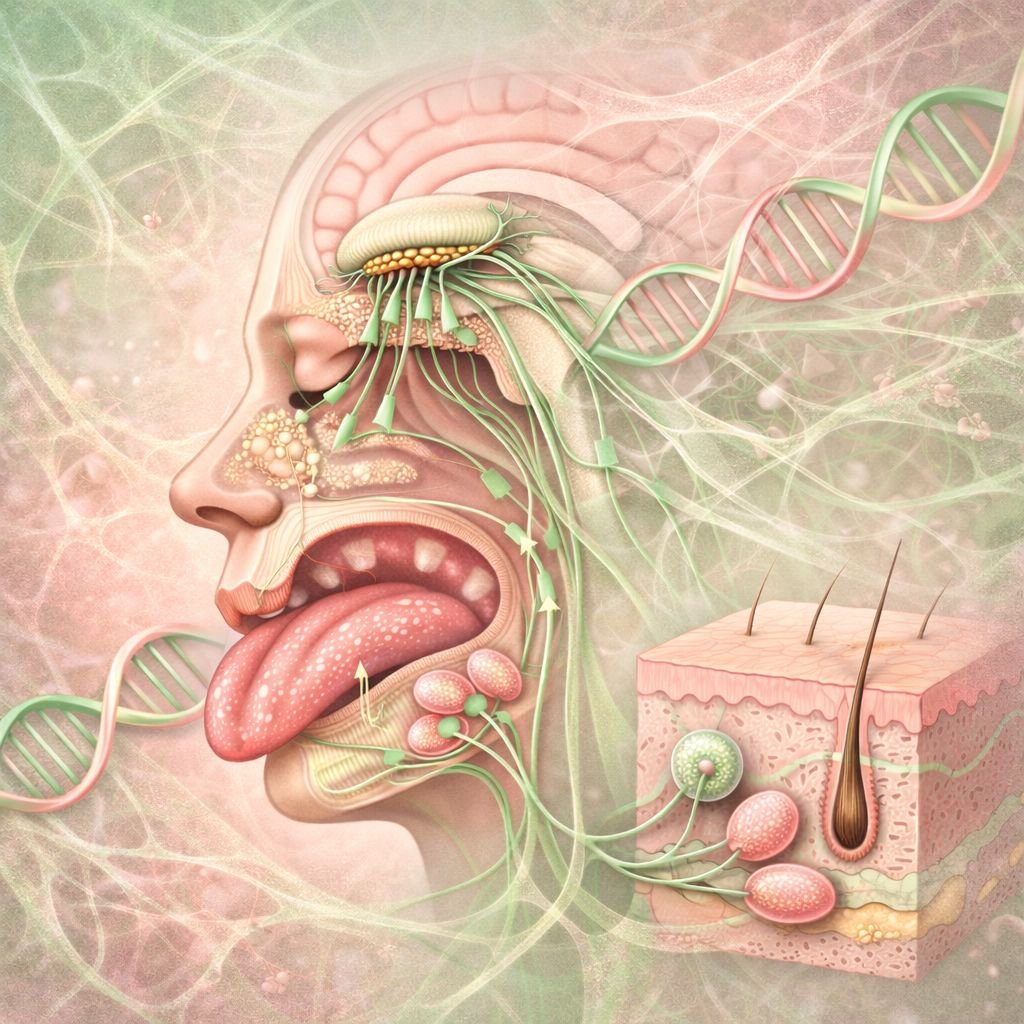

Following the response to the previous exploration of connective tissue in the eyes and ears, this post continues the sensory map through the nose, mouth, face, and touch.

While sensory sensitivities are often framed as behavioural, neurological, or psychological, very few models account for the tissue-based architecture underlying those sensations. Connective tissue plays a structural and bioelectrical role in shaping perception across all sensory domains. Nowhere is this more visible (and less understood) than in the face.

![]() The Nose: Smell and Fascia

The Nose: Smell and Fascia

The olfactory system is deeply integrated with both fascia and the autonomic nervous system. The connective tissue surrounding the olfactory bulb and cribriform plate (a thin, sieve-like bone at the top of the nasal cavity) can influence the transport of molecules and cerebrospinal fluid. This may explain why some individuals have heightened or distorted smell perception. Inflammation, laxity, or subtle cranial structural differences – common in people with hypermobile-type connective tissue divergence – can alter olfactory signalling.

Olfactory receptors live in a moist, mucus-lined epithelium deep within the nose. To smell something, molecules must dissolve into this layer and bind to receptors – which are embedded in a structural scaffold of tissue and supported by the extracellular matrix (ECM). That’s connective tissue.

If that matrix is too permeable, fragile, or inflamed, it alters the sensory landscape completely: smell becomes muted, distorted, or hypersensitive. Many divergent individuals report extreme reactions to smell – not just aversion, but overwhelm. This may reflect not only brain-based pattern recognition, but altered signal strength at the very root of olfactory detection.

In addition, olfactory neurons are directly exposed to the external environment, bypassing the blood-brain barrier. This makes them vulnerable to environmental toxins, pathogens, and oxidative stress – a vulnerability that may be amplified in individuals with less robust connective tissue scaffolding.

![]() The Mouth: Tongue-Tie, Palate, and Collagen Signalling

The Mouth: Tongue-Tie, Palate, and Collagen Signalling

The architecture of the mouth is often overlooked in sensory and developmental assessments. The lingual frenulum (the connective band under the tongue) varies considerably between individuals.

On one end of the connective tissue spectrum is tongue-tie (ankyloglossia), where the frenulum is short or tight, restricting tongue movement. On the other end is an often-overlooked phenomenon seen in some individuals with Ehlers-Danlos or related connective tissue conditions: a lax or even absent frenulum. This can also be accompanied by soft oral tissue, poor muscle tone, or delayed oral-motor coordination.

Other midline variants – like bifid uvula, submucous cleft palate, or high-arched palate – are frequently overlooked, yet they often co-occur in collagen-related conditions and may subtly affect speech, feeding, and sensory integration.

These variations reflect broader shifts in tissue integrity and coordination, with downstream effects on feeding, speech, taste, and breath control. The hard palate and soft palate can also show signs of structural variance – high-arched or soft/drooping palates being common among neurodivergent populations. This may affect nasal resonance, chewing, or even breathing during sleep.

Taste receptors are housed in mucosal tissues embedded in a collagenous matrix. Inflammatory signalling, mast cell activation, or altered tissue perfusion can all affect taste perception – something often missed in clinical or behavioural framings of food aversion.

![]() Touch: Skin, Fascia, and Mechanosensation

Touch: Skin, Fascia, and Mechanosensation

The skin is the body’s largest sensory organ, and its responsiveness is shaped by more than just nerve endings. The extracellular matrix, including collagen and elastin, plays a role in how mechanical stimuli (like pressure, texture, temperature) are received and transmitted. People with altered collagen expression may experience touch as painful, itchy, irritating, or even electrically charged.

Connective tissue also plays a major role in proprioception (body awareness), as fascia houses sensory receptors that help regulate movement and positioning. Loose or dysregulated fascia can contribute to sensory processing challenges, clumsiness, or hyper-awareness of internal sensations.

Mechanosensitive ion channels like Piezo1 and Piezo2, embedded within connective tissue scaffolds, play key roles in translating pressure into neural signals – meaning that connective tissue tone directly modulates how we feel the world.

![]()

![]() A Spectrum of Expression

A Spectrum of Expression

As with neurodivergence itself, connective tissue variation presents across a spectrum. Not everyone will have every trait – and some will show only subtle signs that go unrecognised by typical diagnostic thresholds. However, when we zoom out and connect these micro-features across systems, the pattern is unmistakable.

We need a new language for these patterns – one that dissolves artificial divides between neurology, anatomy, and perception. A language that recognises connective tissue as both sensor and signal; a terrain in which biology, ancestry, and environment co-produce experience. Without this shift, we will continue misreading sensory divergence as pathology rather than divergent and varied physiology.

Connective tissue is not just a structural element. It is part of the sensory terrain.

Divergent genomics by Neurotopia private social media group link:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1305414697616716/?ref=share

#neurodivergent#neurodiversity#autism#adhd#science#biology#physiology#anatomy#sensoryprocessing#sensory#skin#connectivetissue#divergentgenomicsbyneurotopia#EDS#collagen